Our Positive Periods Program is successfully tackling Period Poverty all over the world

What is our Positive Periods Program?

How it all started

Where are we now

The Gambia

The Foundation has been working with teachers and educators in The Gambia and Sierra Leone over the past 3 years to pilot a project to enable girls who miss 50 days a year due to having their menstrual period access to reusable period pads. We have called this project “Positive Periods”.

We were invited by the Gambia Teachers Union (GTU) initially to pilot this project and since then we have carried out research on the most effective and sustainable way for all girls to access this opportunity.

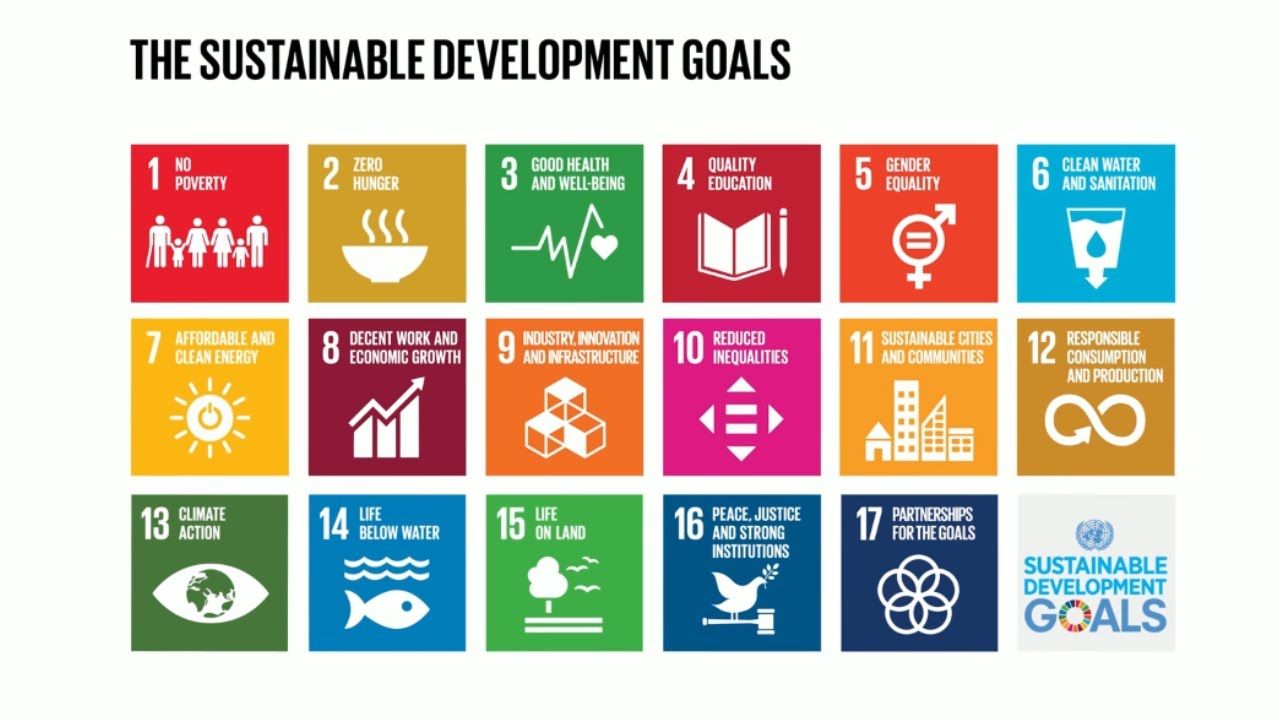

To tailor this program to the unique needs of girls the organisers have added in a module to raise awareness of sexual violence and gender equality.

The teachers who have had this training are cascading this training throughout their schools.

Sierra Leone

In Sierra Leone, Isata M Kamara (project Manager) working with the Sierra Leone Teachers Union (SLTU) and other community groups has hosted this programme in over 60 schools this year in Makeni, Port Loko, Bo and Kenema.

Despite the COVID19 outbreak leading to the closure of schools affecting the implementation of this training taking place in schools, the teachers were determined to ensure the Positive Periods Program did not stop altogether.

Boys and girls, and women and men were all involved in the workshops. They were trained in using both their hands and sewing machines to ensure that that everyone in their various schools could prepare the sanitary pads themselves and cascade this to others.

The training was initially based on health and hygiene, how to take care of themselves, and how to take care of the pads. But as the girls in her workshops talked to Isata about their problems and challenges, she realised that there was more that needed to be done. They asked for training to support themselves and their teachers on the gender-based violence and equality issues that are affecting them in their schools and community. So the organisers have now devised an additional module to raise awareness of sexual violence and gender equality to these workshops.

Plans for the future: Everyone is learning together and supporting each other, women and men, boys and girls. There is still much work to do and the team are now working on the most sustainable way of sharing the learning with other schools and communities across rural Sierra Leone.

Cuba

In March 2021 we started the Cuba Positive Periods Programme, named “Iniciativa Duenas” which is part of our initiative to train people in the preparation of reusable sanitary pads or intima as they are called in Cuba. The project is about how to make re-usable pads using sustainable, reusable and washable, long lasting and eco-friendly material. There were also benefits for more senior women, for those who need support with incontinence, and following surgery.

It incorporated discussion and learning across the generations with grandmas teaching their grandchildren.

The participants came together on-line from across 15 women's entrepreneurship and anti-racist struggle groups. They were instructed and communicated with each other through WhatsApp. These sessions took place from their homes, in the provinces of Havana and Santiago de Cuba. The workshops facilitated a space for conversation not only about how to make their own reusable period pads but also about menstrual health for young people.

These women will now spread this workshop in their own groups and encourage other women to share it too. This way it will reach more women than we could possibly reach alone.

Haiti

July 2021, in Haiti the project started a few days after the political situation became tense, you can read more about this in our blog post here. If that wasn’t enough during the project there was an earthquake, we ran an appeal for this too. We were not sure if the project would be able to start or continue due to these challenges, however the Haitian spirit shines in the face of any adversity, and they continued regardless. A lighthouse for us all to follow. This program also decided to add in a module of sexual health, pregnancy and gender rights, as that was a related topic very pertinent to the current needs of girls in Haiti right now.

Stelandie Jean-François, the young woman in charge started the session introducing the materials the girls would be using and the patterns that they will use to create their own re-usable pads. Her students had no experience sowing so they were learning this skill also. They are very excited to be getting hands on experience making period pads that will help them live a fuller life, and come to school every day.

In the meantime, the school nurses drafted the training modules that they will be using for the next phase, the educational sessions. This will ensure that girls and young women know more about menstruation and female health. This supports them to better manage and understand their menstrual health and wellbeing.

After this workshop was delivered, staff can be trained on the workshop, and how to deliver it in their respective schools. This way the knowledge is cascaded through to the wider community.

Thank you to our Sponsors

We could not carry out this work without the support of our sponsors Soroptimists International St Albans and District, London Chilterns, Leeds and Selby. NEU Districts and Branches and all the incredible individual donors who support us with regular giving and one-off gifts.

We have also recently secured generous funding from The Openwork Foundation, so we can continue to expand this program to other countries.

Plans for the Future

We know this programme works, the feedback from participants has been very positive, they have been instrumental in improving and adapting the training. The most important impact has been the feedback from teacher’s that girls are now coming back to school and they feel they are able to talk about their periods more openly and share solutions.

We have learned that the programme can be replicated and adapted for different needs and it is giving women and girls a voice about other important issues such as gender-based violence. If you have equal access to education you have equal choices.

We are just waiting to roll out the programme in Malawi and Uganda, which has had to be be postponed due to Covid-19. We have 6 other countries waiting to start the programme and the teams are working on sustainability in each country. This project enables women and girls to manage their periods with dignity and pride, it’s a simple solution but we know it is a powerful one.

We hope you will continue to support us on this journey.

More blog posts about our Positive Periods campaign

Sierra Leone Positive Periods

Positive Periods Enable Education

Positive Periods workshops start in Haiti

Why don’t girls go to school?

Promoting gender equality and safe learning environments in schools

Cuba Positive Periods

Videos about our Positive Periods campaign