Blog

On 23rd January at the Cima Community School of Hope (ECEC), the first workshop was held with the first group of students as part of the STEM program. This activity marks a promising start to the program's implementation. STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) is crucial for children because it fosters critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity from a young age. It nurtures natural curiosity, helps children understand the modern world, and builds resilience through hands-on experimentation. Additionally, early STEM exposure prepares them for future academic and career success. A total of 20 students participated in this first session. The session focused on a general presentation of the importance of computer programming in today's world. The students were also introduced to the Scratch software interface, an educational tool well-suited for teaching children programming. This initial experience went smoothly and generated considerable interest and strong motivation among the students.

At the Steve Sinnott Foundation, we know that planning for the future is one of the most important things you can do for the people and causes you care about. That’s why we’re delighted to offer our staff and volunteers the opportunity to write or update their will this Spring. Whether you’ve been meaning to get started for years, or you simply need to make a few updates, this is the perfect time to take that important step. Join Our Free Will Writing Webinar To help you get started, we’ve partnered with expert estate planners Octopus Legacy , who will be hosting a free webinar(s) covering everything you need to know about writing or updating your will. Staff & Volunteers 12pm, Thursday 5th March Online via Zoom - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_uvirWft7S12lJUby6oUtnQ#/registration Supporters 12pm, Tuesday 10th March Online via Zoom - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_xxJNZd6ZQYKMOs-2fNz0Gg#/registration During the session, you’ll learn: Why it’s important to have an up-to-date will What to consider when writing or updating your will The different types of will-writing services available How Lasting Powers of Attorney work and why they matter How to claim your free will this Spring This webinar is designed to make what can feel like a complex process simple, clear and manageable. Why Having a Will Matters Having an up-to-date will ensures your wishes are respected and your loved ones are protected. Without one, the law decides how your estate is distributed and that may not reflect what you would have wanted. A will gives you peace of mind. It allows you to: Provide clarity and security for your family Appoint guardians for children if needed Make specific gifts to individuals or causes Ensure your estate is handled efficiently Updating your will is just as important as writing one. Life changes marriages, children, property purchases, or changes in circumstances can all affect your wishes. Claim Your Free Will This Spring As part of this initiative, eligible staff and volunteers will have the opportunity to claim a free will-writing service. Full details will be shared during the webinar, including how to access this benefit. We encourage you to take advantage of this opportunity. Writing or updating your will is one of the most responsible and caring decisions you can make for yourself and for those you care about. Register Now Spaces are available now, simply register using the link below: Staff & Volunteers - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_uvirWft7S12lJUby6oUtnQ#/registration Supporters - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_xxJNZd6ZQYKMOs-2fNz0Gg#/registration We hope you’ll join us on Thursday 5th March and take this positive step towards securing your future.

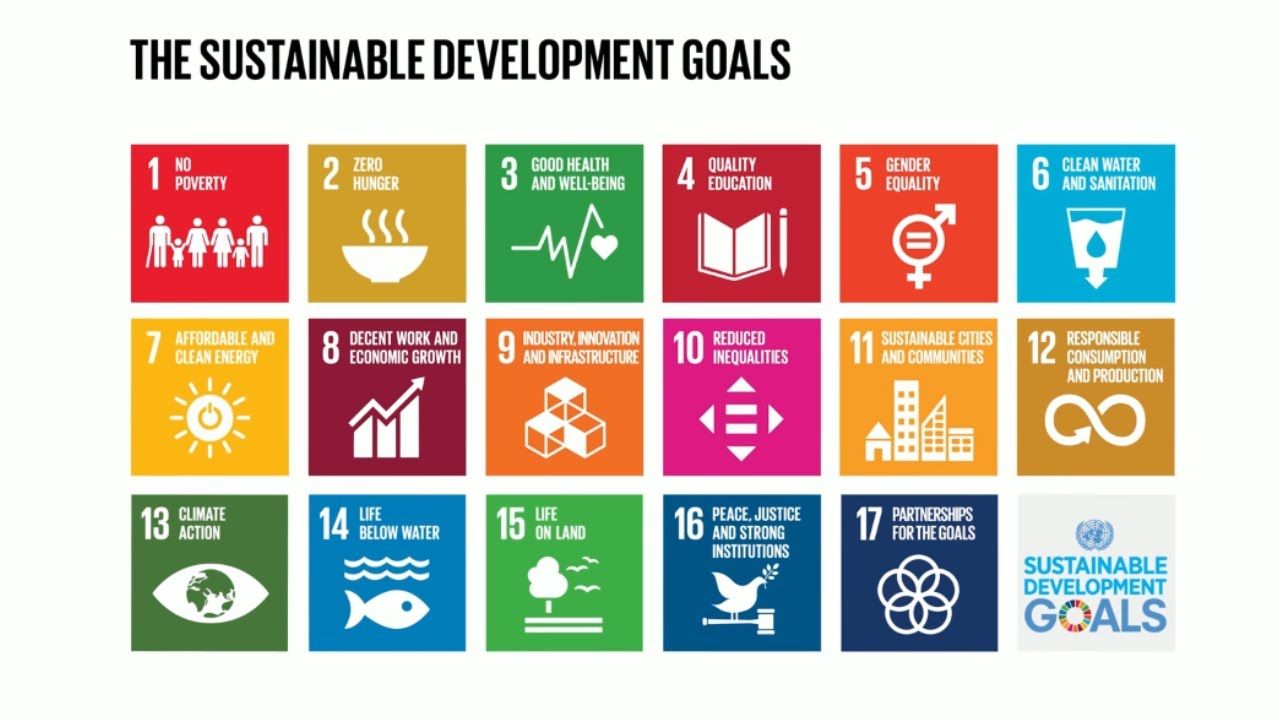

In my time as an assistant at The Steve Sinnott Foundation (SSF), one of my research tasks was looking into how the Foundation contributed to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). I really believe in the work of the Foundation and I have also been raising funds as I believe that every child must have the right to education. SSF is a UK-based educational charity focused on promoting quality education worldwide. It plays a supportive role in achieving the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially Goal 4: (Quality Education), but its work contributes to several others as well. Here's how the Foundation supports the SDGs: Goal 4 – Quality education (core focus) The Foundation's main mission is to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. It supports teachers and educational initiatives in developing countries. It runs programmes like: The Education for All Campaign – advocating for universal access to education. Teacher empowerment projects – providing training and resources to educators in under-resourced countries. Girls' education programmes – encouraging and supporting girls to stay in school and complete their education. Goal 3 – Good health and well-being Through education, particularly health-related programmes, the Foundation contributes to raising awareness about hygiene, nutrition, and mental health. The Foundation has developed a range of webinars to promote health and wellbeing and these can be found on YouTube. Goal 5 – Gender equality The Foundation promotes girls' education, directly addressing barriers that prevent girls from accessing and completing school. It advocates for the rights of women and girls, especially in patriarchal or disadvantaged societies. Goal 8 – Decent work and economic growth By improving access to education and vocational training, the Foundation helps create employment opportunities. Educated individuals have better chances of securing decent work. Goal 10 – Reduced inequalities It supports marginalised groups, including children in rural or conflict-affected areas, contributing to reducing global inequalities in education. Goal 16 – Peace, justice and strong institutions Promotes education as a force for peace and conflict resolution. Supports democratic participation and awareness through educational programmes that foster community engagement. Goal 17 – Partnerships for the goals Collaborates with NGOs, unions, schools, and governments to deliver and advocate for education projects. Builds international partnerships to achieve the SDGs through education. Summary While The Steve Sinnott Foundation's primary focus is on Goal 4, it contributes to many of the SDGs by empowering communities through education, particularly: Gender equality (Goal 5), Health (Goal 3), Economic growth (Goal 8), Reducing inequality (Goal 10), Peace (Goal 16), and Partnerships (Goal 17). The Foundation’s programmes also contribute to the achievement of other SDGs through the power of the provision of education and life-long learning; 1. No Poverty, 2. Zero Hunger, 13. Climate Action. We believe that all of the 17 SDGs are only achievable by ensuring that all children, wherever they are born, deserve the human right of quality education. Over 250 million children are still out of school and the global out-of-school population has reduced by only 1% in nearly ten years, according to the UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report 2024. There is still much work to do in achieving equitable and quality Education for All.

As the founding Headteacher of two start-up schools in Oxfordshire, one primary and one secondary, we spent a lot of time thinking about our new schools’ vision, mission and values. We were deeply committed to becoming values-based educational settings. We also did a lot of work on our global citizenship curriculum which formally brought together all of the loose threads in what Dr Neil Hawkes calls the ‘inner curriculum’. Working towards UNICEF’s Rights Respecting School Award to demonstrate our intentional teaching of the UN’s SDGs was a fundamental part of our commitment to our school communities. When I left headship to move #DiverseEd from being a grassroots community to iterating into Diverse Educators, a Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging (DEIB) training and consultancy organisation, I thought once again about how our work supported the education system in working towards the SDGs and we outlined them here: www.thebelongingeffect.co.uk/the-sustainable-development-goals Five years on, we have just gone through a re-brand, and we are now called the Belonging Effect. For me the strategic intention we take towards developing consciousness, confidence and competence in DEIB must be actionable and must have impact. So our renewed mission is ‘shaping intention into impact’

Summer of 2025, I volunteered in Lusaka, Zambia with Mission Direct to improve educational facilities for school children and staff. These nursery school children live in very basic and small homes in the Kaunda Square Compound. They are currently being educated in overcrowded classrooms with very little space for play and movement. The new school building will allow more children to benefit from an enriching nursery education and ensure that they are ready to learn when they start their formal schooling at the age of six. It will also enable more mothers to work and contribute to their families’ income. The children were very happy to meet us and performed a wonderful song with actions to thank us. Witnessing the challenges of these families living in poverty led me to reflect on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that finding a route out of poverty (SDG1) often starts with a quality education (SDG4). Educating children to become literate, numerate and confident, responsible young people allows them to obtain secure employment with fair pay and to have the prospect of rewarding careers, leading to economic growth (SDG8). Of course education is about so much more than preparation for future employment. An educated person is better prepared to maintain the health and well-being of their family (SDG3) and ensure that nourishing food is provided everyday (SDG2). We are disappointed and saddened to learn that some of the world’s wealthiest nations are slashing their overseas development budgets. This makes the work of NGOs even more vital as they strive to reduce inequalities (SDGs 5 and 10) to ensure that all children benefit from a quality education.

Addressing SRGBV comes through different methods. One effective approach is to provide the most at risk of becoming victims with required skills and knowledge. The essence of this approach is to keep girls safe, engaged and ensure before they return to school that they have a better understanding of SRGBV. The phenomenon of school-related gender-based violence [SRGBV] undermines the right to education for countless children, particularly girls. In the initial phase of our project, we successfully implemented SRGBV awareness and prevention programmes in 14 schools across Bombali district Northern Region. Phase one involved training school staff, engaging students, and building community awareness to create safer school environments. This phase focused on training girls to make reusable sanitary pads and other soft skills to engage them in daily activities. The project engaged over 50 students between the ages of 12-18 years in skills training to help keep them engaged in learning how to make reusable sanitary pads, bead design and cake making. The overall implementation of the project was a success as all of the girls engaged were able to learn new skills and new knowledge relating to GBV prevention. Below are some of the specific successes; Girls were trained in making reusable sanitary pads, sewing and bead design work, basic cake making skills, learning to identify violence, report it and learn how to prevent and de-escalate violent situations and how to stay positive in life through mentoring and supporting each other. This increased the knowledge of community stakeholders and parents on the impact both in and out of school. 100 participants including parents, education officials and community leaders were engaged. Despite the successes recorded, there were some challenges in the implementation. Challenges The rains were heavy and affected some classes Inflation in the market affected the proposed initial costs and the current cost of items The number of stakeholders and parents engaged were more than the proposed number leading to an increase in the food budget BY ISATA M KAMARA DIRECTOR OF GENDER EQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT FOR SOCIAL ACTION (GEDSA)

Alfa Limonade, Haiti For all our people who were deprived of childhood education, the objective of this Alfa programme is to provide the opportunity to become literate. In Haiti, especially in rural areas such as ours, literacy rates are dismal. 44% of Haitian men and 56% of Haitian women are illiterate, but these statistics are far worse in villages and the countryside. (UNESCO) Launched 23 years ago, Alfa uses an excellent participatory text book, Goute Sel, for writing, reading, and comprehension. It was developed specifically for use here in Haiti. We also use Ti Koze Sou Istwa Peyi Ayiti, stories and questions from Haitian history, and Lekti Net Ale, reflections on connecting with the world. Through blackboard instruction and Kaye Kalkil, Alfa participants practise exercises in arithmetic. At the second level we launch group discussion through reading Edikasyon Civik. After long consideration, our team of monitors has established that Alfa must develop its own practical introduction to numeracy for adult learners. Our improved numeracy project must adjust to the situation of Alfa participants. Obviously, in their daily lives our participants constantly face numeracy problems. Having no education, they were unaware of their lack of capacity. Today, through Alfa, they are gaining in literacy, and we should also ensure that, despite their often advanced ages, they also become numerate. They must not lose this gift simply because they have been deprived of the basic human right to education. Through our new tool, Alfa’s market women and peasant farmers will grasp the basics of numeracy, so that they are not lost in the economic situations of their adult lives. They will address these problems with awareness, papers and pencils in their hands - just as others do! Chancy Jacques, Alfa Supervisor, and Antolius Pierre, Alfa monitor in Jede, are collaborating on Alfa’s own book, Kalkil San Limit, with the following objectives: To support our monitors with a good tool for introducing numeracy. To reinforce the capacity of every Alfa participant. To enable participants to reflect productively. To enable participants to calculate well and fast. To enable participants to record their written results. Thus Kalkil San Limit will include the following sections: numeracy, problem solving, geometry, and mental calculation. Numeracy is a key part of the core skill base of a literate individual. In our Haiti, this means the ability to understand and use basic maths in real life situations at home, in the market place, or for agricultural transactions. We are preparing to go to print this summer! By Sarah Grey Alfa Limonade, Haiti

Here we hear from Gabie Aurel who leads the Sonje Ayiti Organization (SAO), our partner in Haiti. They prioritise investing in quality education to break the cycle of poverty, promote long-term economic and social stability, and uplift everyone. It equips children, youth, and adults with the skills to achieve their potential, higher earnings, and better health outcomes. SAO’s work improves community well-being overall and fosters a more resilient and inclusive society. Gabie says,’I am so privileged to grace the path of many inspiring individuals (children, youth, men and women) who share their stories about what education means to them and how it has built their confidence and drastically transformed their lives.’ An example of a life transformed is Rosenie Selmour, a second level participant in ALFA at the Cima Literacy Center in Limonade, Haiti. Here is her testimony: ‘I always felt small when people were reading and writing around me because I couldn't read or write. I was afraid to speak in public, and I was ashamed to say that I couldn't read. Since coming to the Cima Literacy Center, my life has changed. Every day I learn something new. I can read on my own, I can read medical prescriptions, I can read my Creole Bible very well, and even write my children's names on their notebooks and supervise their homework. I am in awe to see how our good education is expressed daily in the form of mutual respect, solidarity, empathy, camaraderie, and how we support and treat each other now. We don't laugh at people if they make mistakes. We correct and we encourage. I remember the first time I read a sentence in front of the class, everyone in the centre was happy and applauded me. I felt proud, it was the first time I felt so valued. What motivates me to come every day? ‘It's my dream to be able to read and write well and to know my fundamental rights. And above all, I feel like I'm not alone. We are a family at Alfa.’ Stories like this fuel SAO’s commitment to invest in quality education throughout Haiti, especially in rural villages where the most vulnerable children, youth, and adults have no access to basic education. SAO’s commitment to breaking the cycle of poverty through quality education promotes greater employment opportunities which lift families out of poverty, thus reducing heavy reliance on social assistance programmes. It boosts economic growth through a skilled workforce, fosters individual well-being, reduces preventable diseases,and improves overall understanding of health. This can prevent diseases, unnecessary deaths and improve overall well-being. Quality education cultivates important cognitive, social, emotional, and communication skills. This reduces conflicts and improves harmony in communities. Additionally, it helps build resilience to recurring difficulties, reduces gender-based violence prevalent in rural communities, and strives to promote gender equality, building stronger communities and societies, enhancing social stability. In sum, quality education for all creates a recurring cycle of inclusive opportunity for all.’ Supporting the Resource Learning Centre in Haiti Until students return to school in December they are learning vocational skills and they themselves are actively involved in site renovation work We are really proud to see this revival take hold with so much passion and responsibility.

In March 2025, The Steve Sinnott Foundation, in partnership with Sonje Ayiti Organisation and local partners, launched a month-long campaign in Haiti to raise awareness of gender-based violence and empower communities to take action. The campaign launched on International Women’s Day (8 March) at the CIMA Community School of Hope, where over 200 people gathered for a vibrant programme of cultural dances, drama, partner presentations and open discussions. Facilitators from SOSPSY, a Haitian non-governmental organisation providing psychosocial support and mental health services to communities affected by trauma, violence, and displacement, guided participants in exploring hidden forms of violence often accepted as normal. Their sessions created a powerful space for reflection and the sharing of personal testimonies. Through interactive workshops and educational games, students learned about gender equality and how to recognise and prevent gender-based violence, as well as how to support peers who may be affected. They asked thoughtful questions, engaged actively and pledged to become ambassadors for non-violence in Haiti. As part of the Positive Periods Programme, 20 girls received 100 reusable sanitary pads in recognition of their participation. Many attendees expressed gratitude and a strong commitment to take action within their communities. A national voice inspires local action On 12 March, the campaign welcomed Jean Jean Roosevelt, one of Haiti’s most celebrated singers and a champion for women’s rights through his lyrics. He engaged boys at CIMA School of Hope in a gender-based violence campaign by producing a music video about the topic, giving them a platform to speak about respect for women and their role in ending violence. Their voices will now join a growing national movement for equality. Positive Periods: sustainable solutions for girls and the planet The campaign also tied into the Positive Periods Programme, now in its fourth year. Thanks to funding from The Foundation, students at CIMA’s sewing workshop are making reusable sanitary pads, uniforms and traditional clothing. In March alone, 237 reusable pads were distributed in schools and at the campaign’s closing ceremony, helping girls stay in class and reducing waste from disposables. So far, 41 students have been trained in sewing, with 20 already earning income from their skills. This programme not only supports menstrual health but also tackles poverty and environmental challenges by promoting cost-effective, sustainable, reusable products. Reusable sanitary pads have helped reduce school absenteeism for more than 1,500 girls while also cutting waste across 19 rural schools. This year, the sewing workshops at CIMA Community School of Hope expanded the Positive Periods Programme, training 41 students, both girls and boys, in pad-making and other skills. Twenty of these students are now earning an income of 1,000 Gourdes (around $8 USD) per uniform, while also producing reusable pads for women and girls who cannot make their own. Through The Foundation, the Learning Resource Centre provides a Sewing Workshop that is equipped with machines and supplies, enabling students, not only to produce pads but also to develop valuable skills. Designed for durability, these pads can be reused for years, reducing costs, limiting import, and providing income-generating opportunities for students. Monitoring and evaluation The project evaluated both implementation and methodology before, during, and after each intervention. Pre-assessments measured participants’ knowledge of gender-based violence, while sessions ensured understanding and post-assessments allowed questions and discussion. Initially, most participants were unfamiliar with gender-based violence, but by the end, they actively engaged in discussions on issues like men’s authority over women and corporal punishment, showing increased awareness and commitment. Follow-up interviews confirmed retention of key information and a willingness to adopt behaviours that help prevent gender-based violence in their communities. In total, the campaign reached more than 500 people directly and an estimated 5,000–10,000 indirectly through community networks, posters, and social media—spreading vital messages of equality and change far beyond the classroom walls. Looking ahead Evaluations showed that most participants entered the campaign with little knowledge of gender-based violence but left with a clearer understanding and determination to act going forward. Through these initiatives, The Steve Sinnott Foundation is helping young people and communities stand together against violence, build sustainable futures ,and create a more equal, hopeful Haiti. This programme is supported by the Soroptimist International Foundation, a Charitable Trust overseen by SI (Soroptimist International) Limited. By Gabrielle Aurel Director of Sonje Ayiti