The Power Of Education

SSF: My 13-year-old grandson, Kaylem wanted me to ask you, what made you become an activist?

KS: Very good question, first of all say hello and send my love to your grandson.

I was almost his age when I started something concrete at the age of 11. The first spark about the issues related to children came on the very first day of my schooling when I was entering my local government primary school and I saw a boy my age sitting outside the school gate. We were about 5-6 years old at the time. So I spoke to my teacher because I was disappointed that this boy was not with us in the classroom. My teacher was surprised at the question, told me this was a good question and went on to explain that they are poor children that help their families, and this was a common practice. This was almost 60 years ago now.

I was not convinced by this answer and asked my parents and relatives and they told me the same thing. Every morning and afternoon I saw the boy still working, looking at our feet for shoeshine or repair. At the time, because it was the beginning of school, we were all wearing new shoes so there was no question of our shoes needing repair.

One day I gathered my courage and went straight to the boy, he was working with his father. The boy was very shy when I asked him the same thing I asked my teacher and my relatives, so his father answered, “Sir, I never thought about it because my grandfather, my father, my father and I started this kind of work when we were children and now it’s my son’s turn.” Then he paused and said, “Sir, you guys are born to go to school, but we are born to work.”

This was a shock to me. How come some children are born to work at the cost of their education, their freedom, their health? I could not accept it. That day I had a different perspective of the world. The first lesson I learned was that no matter what my parents or teachers say, it may not be right. They have simply been saying the same thing their parents, grandparents and forefathers have been saying. This was knowledge, experience and traditions and customs that passed on from one to another. Some of these are things that are exploitative and abusive. We should have the courage to question it and see the world with a different eye that does not always accept ready-made answers, but ask questions. This helped to build my personality.

Back to the age of 11, my closest friend suddenly dropped out of school, along with some other boys and girls, at primary level. I knew he came from a poor family, and the reason for them leaving was poverty. My friend disappeared from the town because his elder brother could not earn enough to continue staying in the town, so they went back to their village. That made me very sad and I thought something should be done. So on the day of my school results, me and a friend of mine had a plan. We gathered our pocket money and rented a four-wheel cart that was used for fruits and vegetables. My friend pulled the cart while I chanted, “uncle, aunty, mother, grandmother, friends, congratulations! Today your children passed their classes and have moved on to the next grade.”

It was a good idea, but a lot of people did not understand what was going on. After a few sentences a crowd gathered, my friend and I chanted, “think of those children who could not afford to continue schooling because they had no books or money. From now onwards, your child’s books will go to waste. Why not put them in this cart so we can give them to these children?” Everyone liked the idea and within four hours, we gathered over 2,000 books. We had to take many trips to store these books. Then I spoke to my teacher and headmaster, meanwhile the town spread the word about what happened that day. Teachers then began saying they wanted to do more. So we had an idea that we should make a book bank, so that the students in need could borrow these books for the school year and then return them. The selection of these children would be done by the headmasters, and it became such a big thing that people started calling me Kailash the Book Bank Boy. This was the beginning of my activism.

SSF: You have often said that you can use anger to very positive effect, and that there are lots of disillusioned views in the world. Recently climate change has become a major political focus resulting in many young people around the world feeling angry and disillusioned because of the inertia shown by their governments in tackling the problem. However, their disillusionment is being used as a positive force to affect change.

If you had to give young people a message today, what would that be?

KS: You have already answered it. Once you are angry, it should not be negative, it should not be driven by revenge or jealousy or ego or selfishness and so on. It should be driven by the inner call for justice and righteousness so that anger can be converted into ideas and actions.

Pessimism and passivity are the biggest enemies in our society. Young people are full of energy and enthusiasm, full of dreams and aspirations for the future. More importantly they have a strong regiment of truthfulness and ideas. That is the biggest capital in the world, I would say.

Almost 3 billion young people in the world are under the age of 25, this is a massive population. This is the reason I have run the campaign ‘100 Million For 100 Million’. 100 million young children are victims of violence, including slavery, trafficking and child labour. Denial of education and health care are also forms of violence. On the other hand, hundreds of millions of youth are willing to take on some challenges for a better world, but they don’t have the purpose in many cases. So, 100 million young people should be the spokesperson and changemakers for the 100 million left out. For young people I would encourage to visit our website 100million.org and be the changemakers. Changemakers just have to demonstrate it, that the changemaker is inside each one of us. The champion, the hero, the leader, is inside each one of us. Especially among young people, so they should acknowledge that leader from within themselves.

SSF: What effect did winning the Nobel Peace Prize have on your work?

KS: Well, I used to travel in economy class, now the people that invite me tend to bring me in first or business class!

As far as the staying is concerned, I always prefer to stay in the homes of my friends or supporters and so on than staying in hotels. As I am doing right now, staying with a friend in central London. So in this sense there is not much difference.

In terms of work, immediately after the announcement of the Nobel prize, I did not miss the opportunity because the iron was very hot. Everyone was congratulating me including presidents and prime ministers and heads of United Nations agencies and so on. So, I said it is not enough to just praise and congratulate, more importantly we should sit together, and I want to seek something from you. So I began with the Secretary-General of the United Nations, then ex-president Obama, prime ministers from Norway and Sweden, and many more leaders of the world. All with a demand that I had been struggling for some time in campaigning, all the types of child labour, slavery, trafficking, forced labour should be in the development agenda.

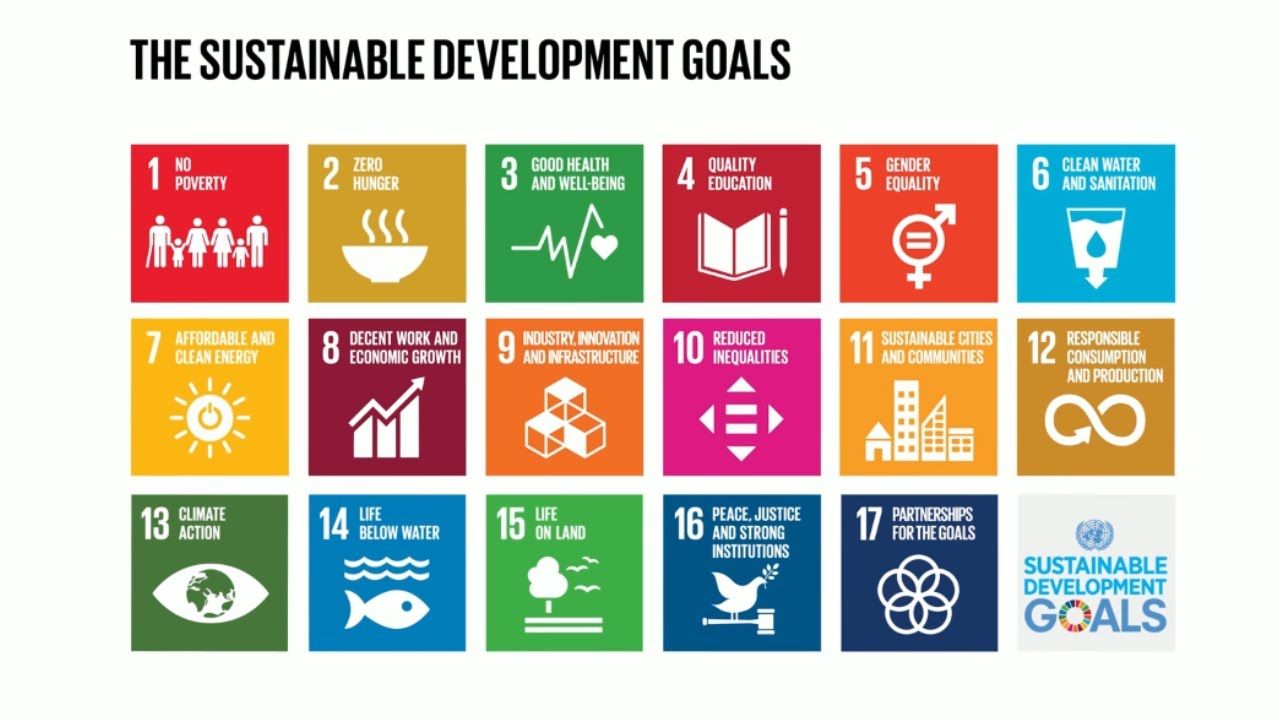

So when we had the MDGs I ran the same campaign, people thought it was a good idea, but nobody listened to those arguments. I have been arguing that, A, without education, you cannot achieve any goal and, B, that you cannot achieve education without eradicating child labour because if children are confined to work in places like factories or mines or farms, then you cannot achieve education for all. Then you cannot complete any of these goals.

But in the case of the SDGs, suddenly the Nobel prize was announced, so everybody was thinking ‘yes that’s a good idea, why not?’ Just the small gold medal and the name tag of being a Nobel Laureate helped a lot. I would say that my personal meetings with the world leaders, and those who supported the idea helped it become a reality.

But we have much work to do and without the commitment to and the achievement of SDG 4 by all governments, we will not achieve a sustainable, peaceful and equitable society or achieve the other 16 SDGs.

Article from Engage 19.