Improving the quality and access to education in The Gambia

Global Digital Divide: Update on Student Research from Brunel University

The problem we have identified is that a lack of resources has led to poor quality of education in The Gambia. We have found through extensive research children in The Gambia are not currently receiving quality equitable and inclusive education in comparison to their international peers, which is a step back in achieving universal access to education SDG 4.

We mapped out a problem tree to try and identify root causes and the effects that poor quality education is having.

A few simplified examples of some of the causes are:

· the outdated and limited textbooks which are limiting the content available because there is a lack of learning resources available as the resources are being allocated elsewhere due to the government prioritising funding to other sectors.

· the lack of Internet access, because there is often no internet signal or coverage due to routers and hubs being few and far between, as there is a lack of technology to make use of the Internet.

· the supply of electricity is often interrupted

· the affordability of accessing learning resources, the internet and electricity for many people.

A few examples of some of these effects are a poor quality education leading to reduced opportunities for learning which leads to a higher drop out rate resulting in incomplete education or no higher education at all, which brings about lower specialisation in industries. Another effect is that if teachers cannot access resources and training the knock on effect is poor quality teaching which leads to reduced opportunities for learning, which results in lower attainment levels among students.

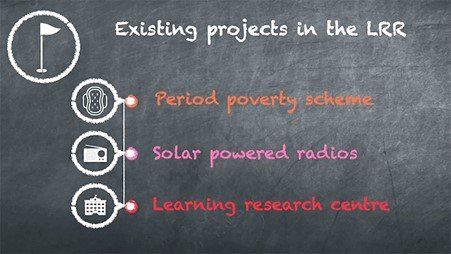

Now we have identified the cause and effects of poor quality education let's look at some of the existing projects in the Lower River Region. The Steve Sinnott Foundation (SSF) has implemented various projects in The Gambia working with various stakeholders including the Gambian Teachers Union.

One project they have documented is the Positive Periods programme, where teachers have been trained to teach women and girls how to make their own reusable sanitary pads from low cost materials. This enables them to go to school while they have their period despite the taboo around menstruation. Impacts of this project involve reduced bullying and harassment of girls due to improved hygiene and maintenance of their periods. This project is already being implemented in schools in the Lower River Region and is proving to be very successful.

SSF have also worked alongside the Gambia Teachers Union to improve access to education during the Covid-19 pandemic the project provided Solar Powered Radios for students in the remote area of LRR to enable access to education through listening to the Gambian governments national broadcast. This helped promote inclusive and equitable education for the regions that had been left behind.

The Steve Sinnott Foundation alongside the Gambia Teachers Union have also started planning the implementation of a Learning Resource Centre which will be located in Banjul. The refurbishment of the centre was been postponed due to Covid-19, but we are now back on track and things are coming together. This will greatly increase the access to learning and research, training and resource provision for teachers. The implementation of new learning devices and the digitalization of education can greatly increase the quality of education available. With circumstances now changing and schools reopening, we have joined forces to look at how we can increase the quality of education provided.

Our initial research looked at introducing Wi-Fi connectivity to the Nemakuta Basic Cycle School in the LRR to increase access to a range of educational information. However, after further looking into it we realised that given the regions environment Wi-Fi doesn't offer a sustainable solution to the problem at large and instead shifted our attention to the classroom learning environment itself.

So we have proposed the following. Simply put the goal is to improve the quality of education delivered in classrooms in the LRR. We define ‘quality’ as a standard of resources, a standard of the curriculum, and a standard of the teaching methods. So, we see that improved resources can facilitate a better teaching method and allow for a wider range of learning materials. Ultimately that will improve resources to ensure that students can expand their skills, their knowledge, and their understanding.

Currently only 10 students in grade 7 achieve above the average of 60% of the assessment marking, while 5 students achieved 75%, so that means that the remaining 30 students fall below the average of 60%. So, in order to reach the goal we set a SMART objective that is specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and timely. Our SMART objective is to increase the average grades students achieve in class so that by the end of the academic year all students are achieving at least 60% of marks in their assessments.

The Gambia Teachers Union are also developing other objectives that can be measured so that we are not just focussing on grades; such as attendance, creativity and positive attitudes to learning and engagement.

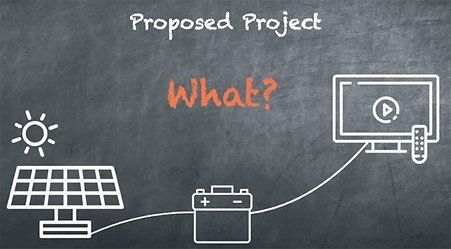

The proposed project that we have outlined is a pilot project in the Nemakuta Basic School with the aim to improve quality education by digitalising the classroom, using sustainable energy. This will provide a solar powered TV screen along with two to four laptops. The solar panel will charge the battery, and the battery can then charge the TV screen and the laptops used in class. The quality of education will be improved through providing pre-recorded content to be shown to students during class the concept will be organised by the Gambia Teachers Union, who will train teachers from the Lower River Region on how to design the learning materials and deliver the lessons effectively.

In the context of our project inclusivity comes from the interactiveness and engagement that allow students to work together. It will allow students to be introduced to digital technology, a wider range of learning materials, along with visual aids. So for the proposed project this will involve 45 grade 7 students at the school along with the teachers of the school.

So how are we going to measure this? At the end of the academic year with a digitalised classroom students achieved grades would be compared to the grades of the previous year to measure the effect of the digitalised classrooms and students learning abilities. The newly achieved grades can be compared with other schools in the region. As education is meant to allow for individuals to access a range of future opportunities our proposal also sees students receiving a holistic education that expands future job opportunities into multiple sectors.

The impacts of our proposal for increased engagement and increased average attainment grades of students, the digitalised classroom environment and technology creates an educational experience that offers a wider range of subjects which can also serve as inspiration to students. Finally an alleviation of the overall burden of the higher student to teacher ratios which will allow for teachers to work more closely with the students.

Our project proposal has a variety of inputs and outputs. Some of the material resources include the TV screen, the solar panel, battery, cables and extension cords, wall mount for the TV, laptops and laptop charges. The human resource includes, purchasing, installation, delivery, research and training. The financial resources are related to funding. The outputs are solar powered energy circuit that powers the TVs and laptops. As well as a digitalised classroom.

The overall timeline of our project plan, we've already executed phase one which saw us conducting a situational analysis to identify the causes and potential solutions. Phase two is expected to run between now and December 18th (2020). We intend on conducting further research into the most viable options so we are looking at which types of devices are most suitable for the classroom environment. Additionally, we're going to begin looking into identifying potential risk and uncertainties about the project proposal.

Phase 3 is set to run from 11th of January to the 2nd of February 2020. Here we will explore ways to mitigate the risk and uncertainties that we would have identified in previous stages. We will also work in partnership with the Brunel Engineering School to set up a mock trial of the solar powered units, to gain an insight into what the teachers and students experience will be. After that we will identify and establish potential costs for the overall project and consult with any experts in the fields where necessary.

Our 4th and final phase is dedicated to refining our project proposal and will conclude the presentation of our overall findings.

The stakeholder analysis - we have a number of stakeholders here on the board. First the grade seven students in the Nemakuta Basic Cycle School these children will be impacted greatly as the first cohort with access to these modern learning devices and also of course if our project is successful then it can be replicated and future students of other schools in the area will benefit.

Next the teachers in the LRR, will have the digitalised resources to provide a different way of learning. The Gambia Teachers Union will be an important part of the project and train teachers on how to use these devices. The Steve Sinnott Foundation who is supporting this project and of course the families of these students.

In summary, our proposal works towards sustainable development goal #4 quality education but also works on sustainable development goal #7 affordable and clean energy. By introducing digital devices that are powered through solar, we hope to see improvements in the quality of education provided, through the digitalization of learning using modern sustainable technology. The pre-recorded content enhance the school curriculum; students will receive information that is more up to date, easy to understand, and not limited to printed materials or textbooks. Additionally, the TVs will alleviate the burden of the low teacher to student ratios in classrooms thus allowing teachers to create a more personalised learning environment.

If successful this can be replicated in schools across the Gambia's region 4, Lower River Region, giving students access to quality and critical education and enabling access to lifelong learning opportunities for all. We'd like to thank you for your time and are there any questions?

Please leave them in the comments below.

Also here are a couple of videos explaining the challenge of accessing education online, and internet access statistics.