By Kaylem James

•

February 3, 2026

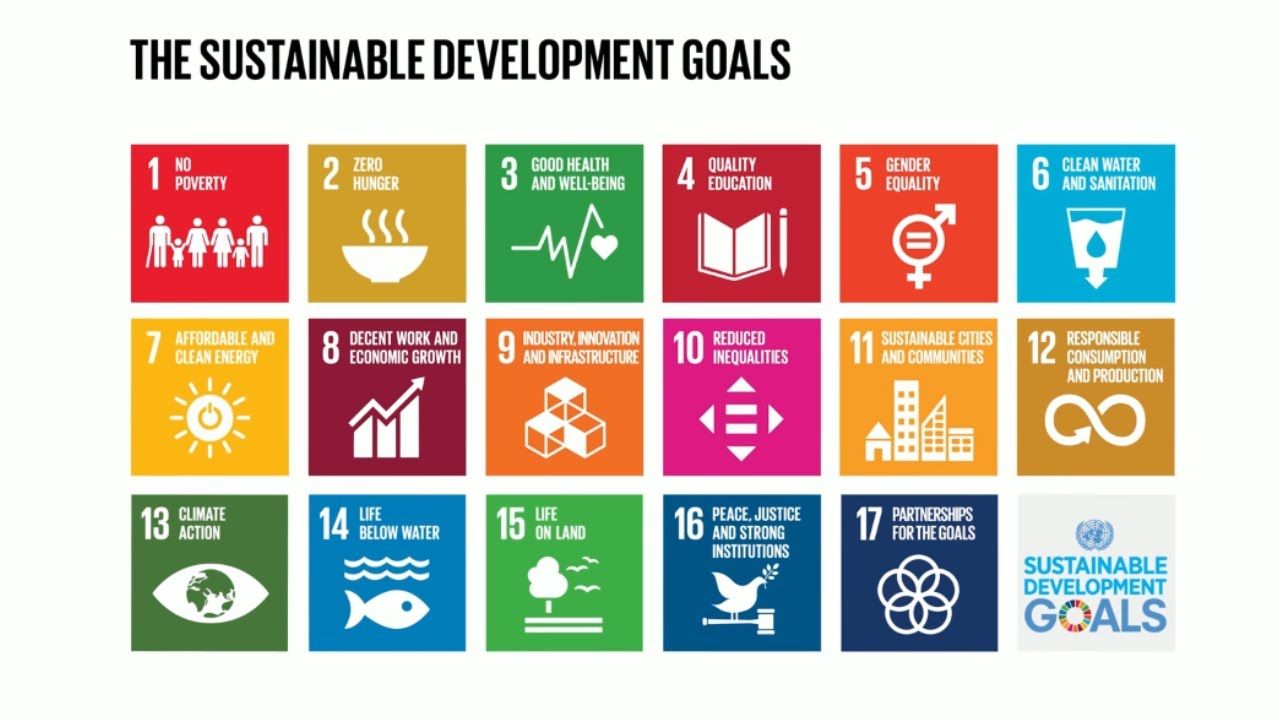

In my time as an assistant at The Steve Sinnott Foundation (SSF), one of my research tasks was looking into how the Foundation contributed to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). I really believe in the work of the Foundation and I have also been raising funds as I believe that every child must have the right to education. SSF is a UK-based educational charity focused on promoting quality education worldwide. It plays a supportive role in achieving the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially Goal 4: (Quality Education), but its work contributes to several others as well. Here's how the Foundation supports the SDGs: Goal 4 – Quality education (core focus) The Foundation's main mission is to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. It supports teachers and educational initiatives in developing countries. It runs programmes like: The Education for All Campaign – advocating for universal access to education. Teacher empowerment projects – providing training and resources to educators in under-resourced countries. Girls' education programmes – encouraging and supporting girls to stay in school and complete their education. Goal 3 – Good health and well-being Through education, particularly health-related programmes, the Foundation contributes to raising awareness about hygiene, nutrition, and mental health. The Foundation has developed a range of webinars to promote health and wellbeing and these can be found on YouTube. Goal 5 – Gender equality The Foundation promotes girls' education, directly addressing barriers that prevent girls from accessing and completing school. It advocates for the rights of women and girls, especially in patriarchal or disadvantaged societies. Goal 8 – Decent work and economic growth By improving access to education and vocational training, the Foundation helps create employment opportunities. Educated individuals have better chances of securing decent work. Goal 10 – Reduced inequalities It supports marginalised groups, including children in rural or conflict-affected areas, contributing to reducing global inequalities in education. Goal 16 – Peace, justice and strong institutions Promotes education as a force for peace and conflict resolution. Supports democratic participation and awareness through educational programmes that foster community engagement. Goal 17 – Partnerships for the goals Collaborates with NGOs, unions, schools, and governments to deliver and advocate for education projects. Builds international partnerships to achieve the SDGs through education. Summary While The Steve Sinnott Foundation's primary focus is on Goal 4, it contributes to many of the SDGs by empowering communities through education, particularly: Gender equality (Goal 5), Health (Goal 3), Economic growth (Goal 8), Reducing inequality (Goal 10), Peace (Goal 16), and Partnerships (Goal 17). The Foundation’s programmes also contribute to the achievement of other SDGs through the power of the provision of education and life-long learning; 1. No Poverty, 2. Zero Hunger, 13. Climate Action. We believe that all of the 17 SDGs are only achievable by ensuring that all children, wherever they are born, deserve the human right of quality education. Over 250 million children are still out of school and the global out-of-school population has reduced by only 1% in nearly ten years, according to the UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report 2024. There is still much work to do in achieving equitable and quality Education for All.