Accessing Education & Schooling

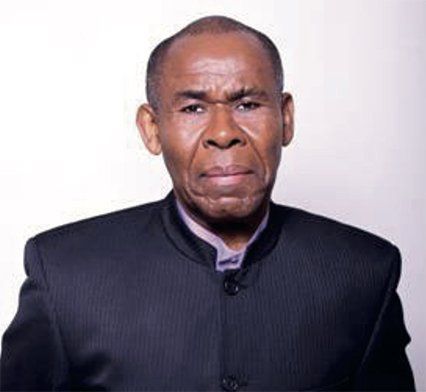

Professor Augustine John is an international consultant & executive coach. A former director of education, he is currently Visiting Professor - Office of Teaching & Learning, Coventry University and Honorary Fellow and Associate Professor, London Centre for Leadership in Learning at the UCL Institute of Education - University of London.

When I had the opportunity to establish a mobile bookshop and book distribution service some 40 years ago, in Manchester, England (home of Manchester United), I named it ‘Education for Liberation Bookservice’.

I was born in a small village in Grenada, Eastern Caribbean, an island with a population then of 90,000. Most of the adults in the village were functionally illiterate, as was my father, or semi- literate like my mother. But, not only were they knowledgeable and wise beyond belief, they were the best teachers I could have wished for and they kept traditions alive, especially oral, spiritual and cultural traditions. It is from them I received my best education, not just foundational education, but education for life and liberty.

What I found astonishing, however, was that the formal schooling and education system looked down upon my village folk and never dreamt of including them in building curriculum, let alone in teaching and knowledge exchange. They were never invited into schools to tell their stories, to talk about their ancestry, to share their knowledge about farming and animal husbandry, their knowledge about the natural world and how they farmed in balance with Nature. Small wonder, then, that they would often tell us as students: ‘Book sense is not common sense’, or ‘schooling is not the same as education’. The task for me in that environment was to respect, value and validate the education I was receiving from them, routinely, in informal and non-formal settings and as Mark Twain famously said, to ‘never let my schooling interfere with my education’.

Thankfully, I was blessed with a rich blend of home schooling – where the entire village was ‘home’- and formal schooling, access to which everyone in the village fought to secure for us as children.

It is for all the above reasons that I developed a strong belief in and commitment to Lifelong Learning and a love of the late Paulo Friere, who was responsible more than anyone or anything else for shaping my education philosophy. I discovered Friere pretty early on in my career and have been guided ever since by his belief in the purpose and function of education as summarised in this statement:

‘Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity, or it becomes the practice of freedom, the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world’.

- Paulo Friere, Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

So, how does education equip people of all ages and at all stages of life to deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world?

If we accept Friere’s premise that education does not change society; it can only change people and it is people that change society, it follows that ALL people have a fundamental right to education. It is not a privilege to be granted on the basis of ethnic nationality, racial or ethnic origin, social class, wealth, religion, age, sex, or physical ability. It is for developing in people the confidence, self-belief, social skills and competences to take control of their own lives, and to function as responsible social citizens, demanding and safeguarding their own rights, while having due regard to and respect for the rights of others.

Whatever denies access to education for individuals and groups in society, irrespective of their identifying characteristics, effectively denies them their fundamental human right and opportunities for self-fulfilment, thus contributing to their oppression.

Education for Liberation is predicated upon education for democratic citizenship. Empowering the individual to develop her/his capacity to act in a self-directing way and to take collective action with others in pursuit of change is at the very heart of the process of managing and expanding a democratic culture.

First published in Engage 23.