Why change needs to be Global

One thing that the Pandemic has illustrated to everyone is how connected we all are to each other. We do not exist in bubbles, our groups are made up of people in other groups, who are connected to more groups and so on. Over the past year and a half we saw the virus spread rapidly across the world. We are all connected across the world.

If we eradicate Covid19 from the UK it will be back in a heartbeat. If we have a vaccination programme in only the wealthy countries, a new variant could bring us all back to square one. We need to eradicate it from the world.

It’s the same for education too. If we are able to get access to quality education right in one country, the problems caused by lack of education are still going to affect people across the world.

Despite improvements over the past decades, progress towards achieving education for all has stagnated and close to 260 million children are not able to access education. In some countries where children do go to school, they are not always able to complete their education.

It is often children from the poorest households, who live in rural areas and particularly girls who are not able to access education.

Marginalisation based on socio-economic status, gender, ethnicity, language, religion and location are all contributors to education inequality. The Covid-19 pandemic has compounded the inequalities children face in accessing their human right to education.

Lack of education, and therefore opportunities, in one part of the world leads to environmental degradation, loss of species, disruption of ecosystems leading to extreme weather and natural events, activities increasing global warming, and viruses jumping species. These things affect the globe.

So in the same way that we have to eradicate Covid19 from the globe, we also have to make education accessible throughout the globe. We are all connected, and a problem created in one place will affect everyone.

We have challenges in the UK and we are all rightly concerned about how we can fix our own problems locally. But we also need to think differently and work on ways to find solutions to problems globally, if we don’t, we will all be adversely affected in a wide range of ways. Working on a global level is a better safety net, and the only truly sustainable way to move forward.

Global change also needs to be achieved at grass roots level, chosen, developed and applied by the local people and culture of each area. It has been proven many times in our partnership work that If people are given the opportunity and work together they can find the unique solution that will work for them long term. That way it is not only sustainable but also is preserving and respecting culture and national differences.

The Steve Sinnott Foundation is working at a grass roots level to make a change to education in our partner areas. We share learning and adapt and replicate projects that allow children and young people access to education and opportunities, which we know from experience make a real difference to peoples’ lives. We will continue reaching out to people, connecting people in different countries, opening an international dialogue about the necessity of Education For All.

Steve Sinnott • August 31, 2021

On 23rd January at the Cima Community School of Hope (ECEC), the first workshop was held with the first group of students as part of the STEM program. This activity marks a promising start to the program's implementation. STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) is crucial for children because it fosters critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity from a young age. It nurtures natural curiosity, helps children understand the modern world, and builds resilience through hands-on experimentation. Additionally, early STEM exposure prepares them for future academic and career success. A total of 20 students participated in this first session. The session focused on a general presentation of the importance of computer programming in today's world. The students were also introduced to the Scratch software interface, an educational tool well-suited for teaching children programming. This initial experience went smoothly and generated considerable interest and strong motivation among the students.

At the Steve Sinnott Foundation, we know that planning for the future is one of the most important things you can do for the people and causes you care about. That’s why we’re delighted to offer our staff and volunteers the opportunity to write or update their will this Spring. Whether you’ve been meaning to get started for years, or you simply need to make a few updates, this is the perfect time to take that important step. Join Our Free Will Writing Webinar To help you get started, we’ve partnered with expert estate planners Octopus Legacy , who will be hosting a free webinar(s) covering everything you need to know about writing or updating your will. Staff & Volunteers 12pm, Thursday 5th March Online via Zoom - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_uvirWft7S12lJUby6oUtnQ#/registration Supporters 12pm, Tuesday 10th March Online via Zoom - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_xxJNZd6ZQYKMOs-2fNz0Gg#/registration During the session, you’ll learn: Why it’s important to have an up-to-date will What to consider when writing or updating your will The different types of will-writing services available How Lasting Powers of Attorney work and why they matter How to claim your free will this Spring This webinar is designed to make what can feel like a complex process simple, clear and manageable. Why Having a Will Matters Having an up-to-date will ensures your wishes are respected and your loved ones are protected. Without one, the law decides how your estate is distributed and that may not reflect what you would have wanted. A will gives you peace of mind. It allows you to: Provide clarity and security for your family Appoint guardians for children if needed Make specific gifts to individuals or causes Ensure your estate is handled efficiently Updating your will is just as important as writing one. Life changes marriages, children, property purchases, or changes in circumstances can all affect your wishes. Claim Your Free Will This Spring As part of this initiative, eligible staff and volunteers will have the opportunity to claim a free will-writing service. Full details will be shared during the webinar, including how to access this benefit. We encourage you to take advantage of this opportunity. Writing or updating your will is one of the most responsible and caring decisions you can make for yourself and for those you care about. Register Now Spaces are available now, simply register using the link below: Staff & Volunteers - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_uvirWft7S12lJUby6oUtnQ#/registration Supporters - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_xxJNZd6ZQYKMOs-2fNz0Gg#/registration We hope you’ll join us on Thursday 5th March and take this positive step towards securing your future.

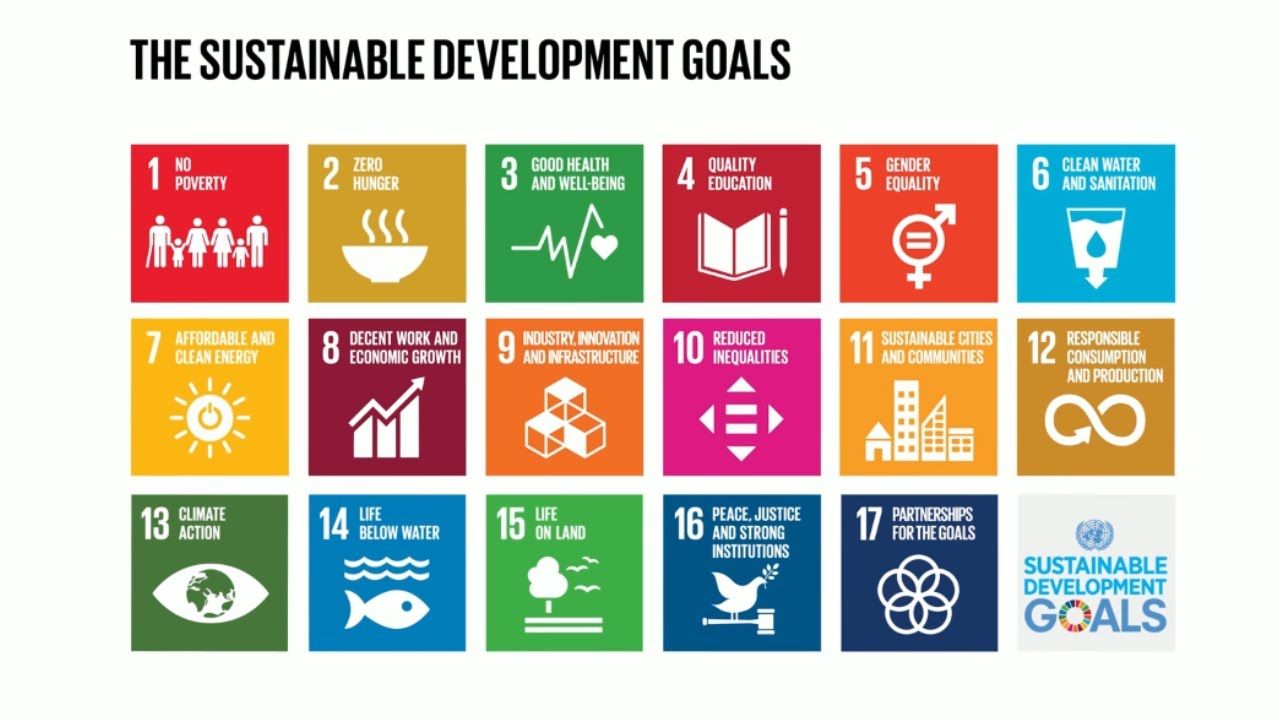

In my time as an assistant at The Steve Sinnott Foundation (SSF), one of my research tasks was looking into how the Foundation contributed to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). I really believe in the work of the Foundation and I have also been raising funds as I believe that every child must have the right to education. SSF is a UK-based educational charity focused on promoting quality education worldwide. It plays a supportive role in achieving the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially Goal 4: (Quality Education), but its work contributes to several others as well. Here's how the Foundation supports the SDGs: Goal 4 – Quality education (core focus) The Foundation's main mission is to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. It supports teachers and educational initiatives in developing countries. It runs programmes like: The Education for All Campaign – advocating for universal access to education. Teacher empowerment projects – providing training and resources to educators in under-resourced countries. Girls' education programmes – encouraging and supporting girls to stay in school and complete their education. Goal 3 – Good health and well-being Through education, particularly health-related programmes, the Foundation contributes to raising awareness about hygiene, nutrition, and mental health. The Foundation has developed a range of webinars to promote health and wellbeing and these can be found on YouTube. Goal 5 – Gender equality The Foundation promotes girls' education, directly addressing barriers that prevent girls from accessing and completing school. It advocates for the rights of women and girls, especially in patriarchal or disadvantaged societies. Goal 8 – Decent work and economic growth By improving access to education and vocational training, the Foundation helps create employment opportunities. Educated individuals have better chances of securing decent work. Goal 10 – Reduced inequalities It supports marginalised groups, including children in rural or conflict-affected areas, contributing to reducing global inequalities in education. Goal 16 – Peace, justice and strong institutions Promotes education as a force for peace and conflict resolution. Supports democratic participation and awareness through educational programmes that foster community engagement. Goal 17 – Partnerships for the goals Collaborates with NGOs, unions, schools, and governments to deliver and advocate for education projects. Builds international partnerships to achieve the SDGs through education. Summary While The Steve Sinnott Foundation's primary focus is on Goal 4, it contributes to many of the SDGs by empowering communities through education, particularly: Gender equality (Goal 5), Health (Goal 3), Economic growth (Goal 8), Reducing inequality (Goal 10), Peace (Goal 16), and Partnerships (Goal 17). The Foundation’s programmes also contribute to the achievement of other SDGs through the power of the provision of education and life-long learning; 1. No Poverty, 2. Zero Hunger, 13. Climate Action. We believe that all of the 17 SDGs are only achievable by ensuring that all children, wherever they are born, deserve the human right of quality education. Over 250 million children are still out of school and the global out-of-school population has reduced by only 1% in nearly ten years, according to the UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report 2024. There is still much work to do in achieving equitable and quality Education for All.