Do we live in the best possible world?

Robin Bevan served as elected national president of the National Education Union in 2020-21, following many years in trade union leadership. A teacher since 1989, a Headteacher since 2007, Robin is committed to ensuring that education in all our schools reflects the values of the future society we would wish to see as a legacy for the next generation.

“Do we live in the best possible world?”

“Have we come to the end of all the changes that our society needs?”

“Should we be working towards a transformed future?”

At the heart of the vision for the school which I lead, as Headteacher, is an expectation that we are working to cultivate a new generation of activist leaders. Our vision is to educate pupils – through the curriculum, extra-curricular provision and the ‘way that we teach and lead’ – to be agents of change: knowledgeable, skilful, empathetic, and committed to worthwhile causes.

Working life with young people in a secondary school can be challenging. There are trends in society that can feel dispiriting. For a decade or more, in the UK, our national leaders have conspicuously failed to communicate a narrative of hope for the future. Indeed, they have – to a large extent – advance their policies on the basis that ‘the past was better than the probable future’.

And yet, sat in front of year group assemblies, I often ask the questions that opened this article. And, without exception, every young person responds positively. Our young people recognise there is much that needs to change. The next generation is clear what needs to be done.

Schools exist for the society that is yet to be. Sadly, in England, education is too often shaped within frameworks that retain patterns of privilege, hierarchy, employment and economic resource. For some, education exists only to leverage personal advancement; for others, it’s there only for employment; and there are even those who see publicly-funded schooling solely as a mechanism to minimise social security payments and limit criminality.

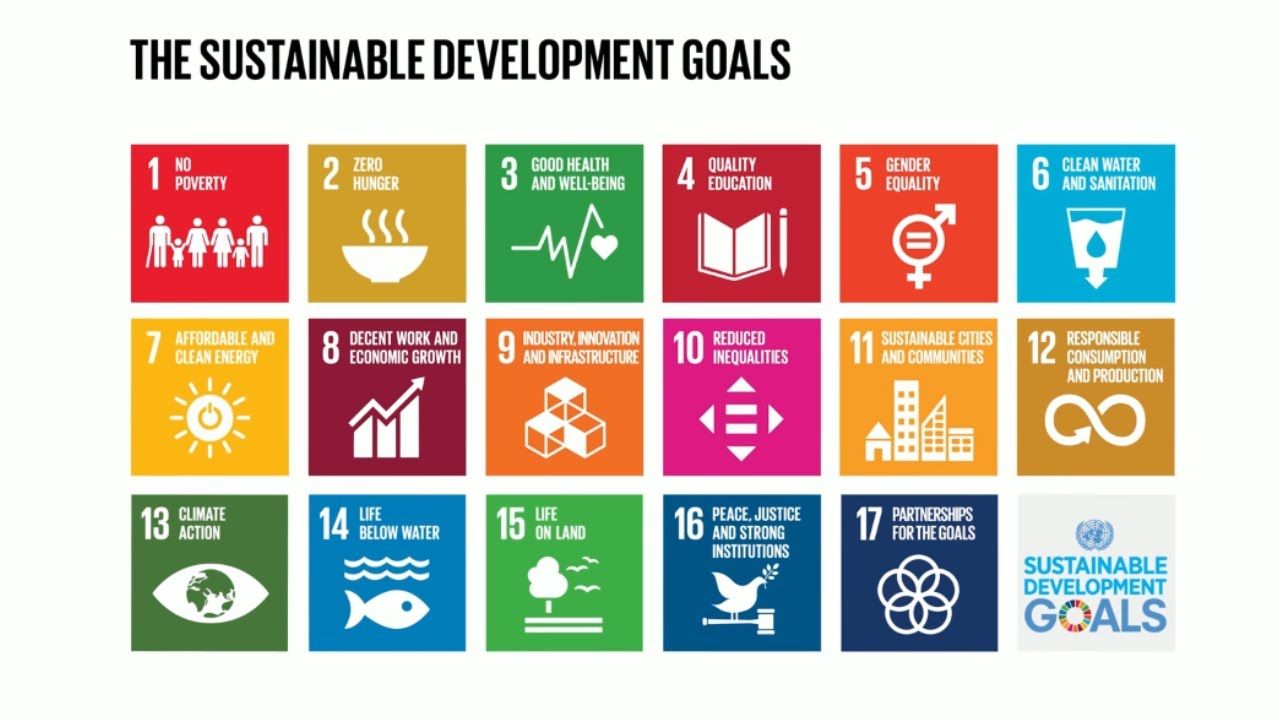

When we ask young people about the best possible future, their answers are compelling. They have varied views, but there are repeated threads. They look to a more international – global – future, with permanently permeable national borders. They speak of the need to address poverty and relative poverty. They know the reforming journey of equality and inclusion is not yet complete: across strands of gender, sexuality and disability. They openly accept the challenge to our global ecosystem and the need for a paradigmatic shift in the use of non-renewables. And so we set out to infuse the school with a culture that welcomes and celebrates diversity. This work has been initiated, developed and led by students: speaking in assemblies, developing displays, organising events on Black History, LGBT+ rights and disability.

Our school openly recognises that climate warming represents an impending existential threat. We set out to reduce substantially the reliance on fossil-fuel transport for school journeys – for students and staff. This work has been shaped and enacted by students: leading cycling events, visiting countries with high levels of cycling engagement, overcoming cultural barriers to bicycle use and dispelling myths regarding the safety of urban cycling.

Our school now has one of the highest levels of daily cycling of any school in the country. We have had to expand secure storage provision to allow for 250 bikes daily.

Our school acknowledges that relative wealth brings privilege, and that – for international trade – this allows Western consumers, unwittingly, to exert purchasing pressure that drives down the market price of cash crops in the country of origin. We set out to promote Fairtrade principles: sourcing, using and selling Fairtrade produce. The relevance of mass campaigns of low-level consumer actions has profound authenticity when our students have worked alongside coffee farmers in India and welcomed a Colombian hill farmer to the school.

If, as Herbert Spencer suggested, the great aim of education is ‘not knowledge but action’ then the greatest pedagogy must be participatory immersion in acts of social change. There is a compelling challenge for all educators: to explore and articulate a clear framework of values for our work, to interrogate whether our provision is consistent with our values, and then to initiate social action projects that align pupil learning to our renewed and purposeful intent.

First published in Engage 24.