Crisis upon a crisis: COVID-19 and the education emergency

Zoe Cohen is the Secretariat Coordinator of the International

Parliamentary Network for Education (IPNEd), the first global

parliamentary network dedicated to education. IPNEd seeks to grow

and deepen political understanding of and commitment to inclusive

and equitable quality education for all.

In mid-April 2020, 1.6 billion children and young people found their

education disrupted. The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic forced

schools and education institutions across the world to close, leaving

learners in over 190 countries to contend with severe interruptions to

their education.

As countries across the world have implemented pandemic-response

strategies, the return to, or continued closure of, schools has remained

contentious. The International Parliamentary Network for Education

(IPNEd) has been supporting MPs to navigate the implications of

COVID-19 for education. Whilst there is no zero-risk strategy for the

reopening of schools, a lot can be done to ensure they are safe places

to learn.

In Argentina, IPNEd member Diputada Brenda Lis Austin has led a

powerful campaign for the return of face-to-face teaching 1, and on

17 February 2021 children from five of Argentina’s regional districts

began to return to school for the first time in almost a year 2. In some

countries, school reopening was strongly prioritised in government

response plans. Sierra Leone, for example, supported by learnings

from the 2014 Ebola outbreak, authorised the reopening of all schools

by 5 October 2020 3.

However, for millions of children, the reopening of schools does not

mean a return to learning. Prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, 258

million children and young people were already out of school 4.

Characteristics including gender, disability and ethnicity have played

a significant role in children’s likelihood to attend and remain in

school. Moreover, 330 million children were in school but not learning

the basics 5.

Children affected by displacement, crises and emergencies face

additional and protracted obstacles to education. In 2019, over half of

all school-age refugee children were out of school 6.

Projections have found that the pandemic will substantially increase

the number of children out of school for the first time in decades. The

Malala Fund has estimated that half of refugee girls in secondary

school will not return to school due to COVID-19 7.

For most children around the world, COVID-19 presented an

unprecedented education emergency. For refugee and crisis-affected

children, disrupted learning is commonplace. For these children,

COVID-19 is a crisis upon a crisis.

Although the global recovery from the pandemic remains

unpredictable, education responses must build on lessons from

COVID-19 to strengthen education system resilience, implement

learner-centred remedial programmes, and retain a focus on the

children left furthest behind.

International support for and investment in Education Cannot Wait,

the only global fund dedicated to education in emergencies and

protracted crises, will also be crucial to securing an equitable return

to learning.

Political leadership at each of the national, regional and international

levels will be vital to ensuring a sustainable recovery from COVID-19.

IPNEd is supporting parliamentarians to champion education,

reaching across political divides, regions and the world. In the National

Assembly of Pakistan, for example, IPNEd Regional Representative for

Asia, MNA Mehnaz Akber Aziz, has been working with her colleagues

to advocate for the prioritisation of education and the furthest behind

in the COVID-recovery.

In a post-COVID world, the political will to ensure children can access

learning must be redoubled.

For marginalised children, and particularly those affected by crises

and emergencies, COVID-19 has not created an education emergency,

it has exacerbated a pre-existing one.

IPNEd is working with MPs to ensure that as the world recovers from

the global health crisis, the education emergency is not forgotten.

With less than a decade left to achieve SDG 4, a generation of children

may never return to school. The international community must come

together and redouble our commitment to ensuring the return to

school and learning truly is, for all.

1

twitter.com/brendalisaustin/status/1359294032376180738?s=20

2

batimes.com.ar/news/argentina/schools-in-argentina-finally-re-open-doors-for-students.phtml

3

snradio.net/ministry-of-basic-education-issues-official-school-re-opening-guidelines/

4

uis.unesco.org/en/topic/out-school-children-and-youth

5

report.educationcommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Learning_Generation_Full_

Report.pdf

6

www.unhcr.org/steppingup/wp-content/uploads/sites/76/2019/09/Education-Report-2019-

Final-web-9.pdf

7

www.globalpartnership.org/blog/displacement-girls-education-and-covid-19

Article from Engage issue 22.

BY ZOE COHEN • July 9, 2021

On 23rd January at the Cima Community School of Hope (ECEC), the first workshop was held with the first group of students as part of the STEM program. This activity marks a promising start to the program's implementation. STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) is crucial for children because it fosters critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity from a young age. It nurtures natural curiosity, helps children understand the modern world, and builds resilience through hands-on experimentation. Additionally, early STEM exposure prepares them for future academic and career success. A total of 20 students participated in this first session. The session focused on a general presentation of the importance of computer programming in today's world. The students were also introduced to the Scratch software interface, an educational tool well-suited for teaching children programming. This initial experience went smoothly and generated considerable interest and strong motivation among the students.

At the Steve Sinnott Foundation, we know that planning for the future is one of the most important things you can do for the people and causes you care about. That’s why we’re delighted to offer our staff and volunteers the opportunity to write or update their will this Spring. Whether you’ve been meaning to get started for years, or you simply need to make a few updates, this is the perfect time to take that important step. Join Our Free Will Writing Webinar To help you get started, we’ve partnered with expert estate planners Octopus Legacy , who will be hosting a free webinar(s) covering everything you need to know about writing or updating your will. Staff & Volunteers 12pm, Thursday 5th March Online via Zoom - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_uvirWft7S12lJUby6oUtnQ#/registration Supporters 12pm, Tuesday 10th March Online via Zoom - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_xxJNZd6ZQYKMOs-2fNz0Gg#/registration During the session, you’ll learn: Why it’s important to have an up-to-date will What to consider when writing or updating your will The different types of will-writing services available How Lasting Powers of Attorney work and why they matter How to claim your free will this Spring This webinar is designed to make what can feel like a complex process simple, clear and manageable. Why Having a Will Matters Having an up-to-date will ensures your wishes are respected and your loved ones are protected. Without one, the law decides how your estate is distributed and that may not reflect what you would have wanted. A will gives you peace of mind. It allows you to: Provide clarity and security for your family Appoint guardians for children if needed Make specific gifts to individuals or causes Ensure your estate is handled efficiently Updating your will is just as important as writing one. Life changes marriages, children, property purchases, or changes in circumstances can all affect your wishes. Claim Your Free Will This Spring As part of this initiative, eligible staff and volunteers will have the opportunity to claim a free will-writing service. Full details will be shared during the webinar, including how to access this benefit. We encourage you to take advantage of this opportunity. Writing or updating your will is one of the most responsible and caring decisions you can make for yourself and for those you care about. Register Now Spaces are available now, simply register using the link below: Staff & Volunteers - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_uvirWft7S12lJUby6oUtnQ#/registration Supporters - https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_xxJNZd6ZQYKMOs-2fNz0Gg#/registration We hope you’ll join us on Thursday 5th March and take this positive step towards securing your future.

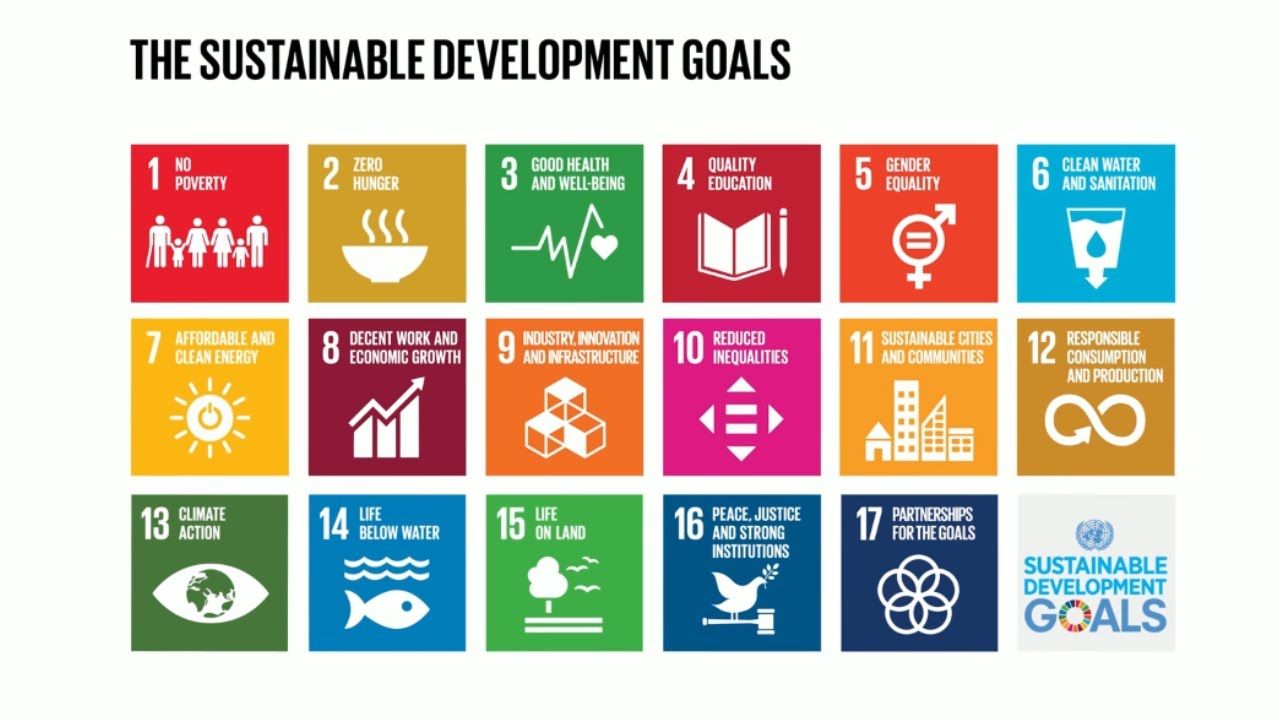

In my time as an assistant at The Steve Sinnott Foundation (SSF), one of my research tasks was looking into how the Foundation contributed to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). I really believe in the work of the Foundation and I have also been raising funds as I believe that every child must have the right to education. SSF is a UK-based educational charity focused on promoting quality education worldwide. It plays a supportive role in achieving the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially Goal 4: (Quality Education), but its work contributes to several others as well. Here's how the Foundation supports the SDGs: Goal 4 – Quality education (core focus) The Foundation's main mission is to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. It supports teachers and educational initiatives in developing countries. It runs programmes like: The Education for All Campaign – advocating for universal access to education. Teacher empowerment projects – providing training and resources to educators in under-resourced countries. Girls' education programmes – encouraging and supporting girls to stay in school and complete their education. Goal 3 – Good health and well-being Through education, particularly health-related programmes, the Foundation contributes to raising awareness about hygiene, nutrition, and mental health. The Foundation has developed a range of webinars to promote health and wellbeing and these can be found on YouTube. Goal 5 – Gender equality The Foundation promotes girls' education, directly addressing barriers that prevent girls from accessing and completing school. It advocates for the rights of women and girls, especially in patriarchal or disadvantaged societies. Goal 8 – Decent work and economic growth By improving access to education and vocational training, the Foundation helps create employment opportunities. Educated individuals have better chances of securing decent work. Goal 10 – Reduced inequalities It supports marginalised groups, including children in rural or conflict-affected areas, contributing to reducing global inequalities in education. Goal 16 – Peace, justice and strong institutions Promotes education as a force for peace and conflict resolution. Supports democratic participation and awareness through educational programmes that foster community engagement. Goal 17 – Partnerships for the goals Collaborates with NGOs, unions, schools, and governments to deliver and advocate for education projects. Builds international partnerships to achieve the SDGs through education. Summary While The Steve Sinnott Foundation's primary focus is on Goal 4, it contributes to many of the SDGs by empowering communities through education, particularly: Gender equality (Goal 5), Health (Goal 3), Economic growth (Goal 8), Reducing inequality (Goal 10), Peace (Goal 16), and Partnerships (Goal 17). The Foundation’s programmes also contribute to the achievement of other SDGs through the power of the provision of education and life-long learning; 1. No Poverty, 2. Zero Hunger, 13. Climate Action. We believe that all of the 17 SDGs are only achievable by ensuring that all children, wherever they are born, deserve the human right of quality education. Over 250 million children are still out of school and the global out-of-school population has reduced by only 1% in nearly ten years, according to the UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report 2024. There is still much work to do in achieving equitable and quality Education for All.